A London office shows insights into 3D prints for architecture

7 min readTogether with some colleagues I built a 3D printer in the mid-late 2000s using plans that we’d downloaded from the internet and sheet components cut-out of acrylic using a laser cutter at the office. It was a really rewarding process as it helped us all to understand properly how the technology worked – as well as being able to laser-etch our names on to the side of the machine as we’d made it ourselves!

More broadly I’ve been interested in the emerging opportunities presented by digital technologies for a long time. Not just in terms of technical performance, but in their ability to provide bespoke solutions at an mass-manufactured prices.

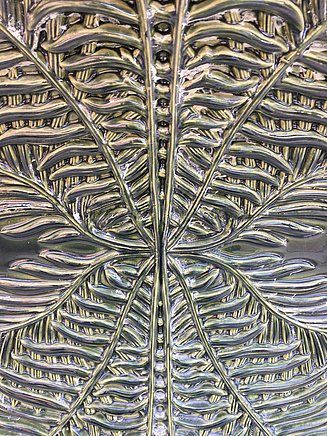

Initially we used 3D printing extensively for model making – for design development models and presentation models. However as the technologies have evolved, our ambitions have grown – both in terms of the scale that can be printed, and the materials that can be printed with. For Ilona Rose House, which is a 30.000 squaremeter building we’ve designed in Central London, we’ve created a façade which includes myriad art-deco rose patterns. The earliest castings for those panels were made at a 1:1 scale in our studio in London’s Leicester Square using moulds created on our suite of 3D printers.

As an early adopter of the technology we were fortunate to be able to provide Beta-Testing feedback to printer manufacturers and filament suppliers for their emerging products. Printing with ‘wood’ for example actually means printing using a normal-ish plastic filament which has been pre-mixed with powdered wood. This acts like an aggregate in the filament which affects the printing temperature, cooling time, viscosity, and selection of print nozzle size. And you don’t want the filament to get so hot that the wood discolours, or even burns. Even the final size and form of the print can have a significant impact as large flat areas can have a tendency to curl up at the edges. That said, once you’ve got the hang of the variables you can produce some spectacular results – and for us that means creating a high quality ‘timber’ model of a building in-studio – which might otherwise have taken weeks if made by a traditional model maker – and cost thousands.

The biggest proportion of the cost is absolutely in the design of the model. Firstly there is the design and construction of the building model. That is a really big piece of work. And then it’s not as simple as just scaling the digital model of the building to print it. Some components (e.g. curtain wall mullions) become too small to print robustly and have to be locally scaled to suit.

The cost of the print materials is generally very low – a few euros and cents at most. Once again the bigger cost is the human part: monitoring the components as they are printed (which can take a long time) and ensuring that whole process goes smoothly.

Architecture is a very plural profession which attracts people from a wide range of backgrounds, technical and or artistic. Part of the joy of architecture is that you often have an interest in, and skills that are both technical and artistic. So I think, the right answer is that the 3D printers end up being experts in both: IT and design as well.

Most of the projects on our website have used 3D printing in some form or another. Perhaps a little unexpectedly one of first uses of 3D printing was to create the traditional moulded white cornices on this project: Grove Lane London

We have used 3D printing both to model – and then manufacture – the façade panels for both of these projects:

I think that this technology has a very bright future – particularly as it gets used on a bigger scale and with different materials. There are already examples of buildings being printed out of extruded concrete and confectionary being printed out of chocolate. You might also be surprised to discover that metals can be 3D printed as well. This is a technology already being widely used for rapid prototyping and manufacturing in the aerospace industry.